Yucatan”s Game

After nearly dying out, the pre-Hispanic ballgame ulama is thriving. March 29, 2023

Different forms of this ballgame have existed continuously in different parts of Latin America for around 3,500 years. (Courtesy of Jose Lizárraga)

In 1968 — on the first day of the Olympic Games held in Mexico City — millions of spectators from around the world watched the ancient game of Ulama, most of them for the first time.

The players are spectacular to watch. The game requires skill, endurance and athleticism — players must leap into the air with great strength, yet with the grace of a ballet dancer as they twist their bodies to hit the ball with their hip.

The Mesoamerican ballgame of Ulama — the oldest continuously played team sport in the world — has existed for 3,500 years. The oldest ball court — discovered in 1974 in Paso de la Amada, Chiapas — dates back to 1400 B.C. Ulama balls have been found that are even older: dating back to 1600–1700 B.C.

Ulama was widespread in Mesoamerica, played by the Olmecs, Aztec and Maya. More than 2,500 ballcourts have been found — the most famous can be seen in Mexico’s archeological sites of Chichén Itzá, Tikal, and Monte Albán.

Ulama reflected the shared cosmological beliefs of a vast region stretching throughout much of Mesoamerica. When the Spanish saw the ritual and its religious aspects and regarded it as a threat to the Catholic Church, they banned the game, and the tradition began to disappear.

By the beginning of the 21st century, historians were concerned that Ulama was becoming extinct. In 2003, California State University and the Historical Society of Mazatlán began a 10-year interdisciplinary project to study the status of the Ulama tradition.

Ulama was documented in 1528 in this drawing by Christophe Weiditz, who was in the audience as indigenous men brought to the court of King Charles V played a version of the game for the monarch.

They found that the game continued to be played in just four communities in Sinaloa but that the practice had died out in the rest of the country, alarming them that this ancient tradition might become extinct.

Then the Lizarraga family almost single-handedly rescued Ulama from extinction.

The family had kept the Ulama tradition alive since 1900, passing down the training and rituals of the game from generation to generation. More recently, family members also became concerned by the lack of interest in the ancient game. They started reaching out to distant relatives and others to provide training and help organize teams.

Don Manuel Lizárraga taught his eight children (including a daughter) to play Ulama, and they exported it to the theme park of Xcaret near Cancún. The park built a ball court and hired players from Sinaloa — at the time, there were no players left in the Yucatán Peninsula — for exhibition games as a tourist attraction.

For the Lizárragas, Ulama is a family tradition. The clan has produced 150 Ulama ballplayers. That tradition is now being carried forward by José Lizarraga, an Ulama player and promoter.

I ask Lizárraga about the symbolism of the game.

“Historically, it was a sacred ritual related to seasonal or agricultural changes, such as marking the beginning or end of a harvesting season. It was also used to end conflicts,” he says.

There are historical records of games played between teams of two civilizations or their kings to decide the winner of a conflict; often, the losing team or king would be sacrificed to the gods.

The Aztecs made Ulama a high-stakes game. Players and team supporters would wager their home, their fields, their children and even themselves — if their team lost, they could lose everything and be forced into slavery and ultimately sacrificed.

Mexicans playing ulama, including Luis Lizarraga, foreground

The Lizárraga family has been a linchpin in saving knowledge of ulama from disappearing. Here, Luis Lizárraga makes a play in a match, date unknown. (David Mallin)

“There is also deep symbolism regarding the creation of the world and the continuous battle of opposites,” Lizárraga says. “Fire and water, good and evil, day and night. The ball court — called a taste (t?s-t?y) — represents the portal to the underworld. The players represent the stars or celestial bodies.

Often, there were ritual offerings to the sacred energies, and the players would present themselves for purification. The game of ulama symbolizes the perpetual movement and duality of the universe.”

INAH archeologist Gibrán de la Torre tells me, “There are three different versions of Ulama: In one, you can only advance the ball by hitting it with your forearm. The second version is to advance the ball with a stick or club called a mazo — similar to the game of cricket. The most popular version is the ‘hip ulama,’ where you can only hit the ball with your hip. It is a continuation of the pre-Hispanic ullamaliztli played by the Aztecs and Mayans.”

In El Quelite, I meet with another Ulama ballplayer, Juan Carlos Osuna, to have him explain how the game is played. I quickly discover that the rules are different depending on the team and the community.

“The ball court is a long, narrow rectangle with end lines, or goal lines, at each end. In the middle is the center line (analco), which separates the two teams. The goal is to get the ball over your opponent’s endline using only your hip,” he explains.

“If you touch the ball with any other part of your body, you lose a point. If it is a low ball, you must drop to the ground and hit it with your hip. I have had many cuts and bruises, but your body gets used to it.”

Osuna raises a cloth sack he is carrying and almost reverently removes a rubber ball the size of a large cantaloupe and hands it to me. The ball is surprisingly dense — weighing almost nine pounds — but it bounces like a much lighter ball.

an artifact ulama ball

Example of a ulama ball on display in Sinaloa. (José Lizárraga)

“The balls are made from the sap of a rubber tree — the arbol de hule — that grows in Tabasco. They must be constructed by special artisans. The technique is passed down from generation to generation.”

The balls are expensive, costing US $1,000 due to the amount of latex required and a scarcity of artisans who know the technique.

Each team consists of three to five players and a referee. Players wear protective gear around their hips — a loincloth, a wide leather belt that straps around their hips and a cloth belt or sash that holds it together and hangs down in front as further protection. The first team to score eight points (rayas) wins the game.

The rules and scoring are so complicated, it can take players years to fully understand them — which is why each game has one or two referees. There are three phases of the game, known as urrias, during you could lose all your points.

Due to the scoring’s complexity, games could have lasted for days — they are now limited to a certain number of hours agreed to by both sides.

Despite all this, Ulama is currently undergoing a serious comeback: through his organization FEMUC Ulama de cadera, Lizárraga has trained and organized teams and tournaments in 11 states in Mexico, as well as in California and Guatemala.

Members of a Ulama team in action.

The game’s rules are complicated and in this version seen here, players drive the ball with their hips. (Courtesy of Jose Lizarraga)

He now has eight women’s teams, 12 men’s teams, four for children and four for youth.

Games can be seen regularly at the Xcaret theme park in Playa del Carmen and at the Xachikalli cultural center in Mexico City. You can even request an exhibition game by contacting Lizárraga at 984-166-8181. Or contact him on Facebook at FEMUC ullama de cadera.Enter your description

Mayan proposed to join Spanish as an official language in Yucatán Carlos Rosado van der Gracht April 18, 2023

An initiative presented this week in Yucatán’s Congress seeks official recognition of the Mayan language in the state.

Advocates of the move argue that such legislation would help to guarantee the linguistic and cultural rights of Maya communities here.

Such a move would not be merely symbolic. If approved, it would require all state services to be offered in the Yucatec-Maya language alongside Spanish.

This would mean that a massive amount of Yucatec-Maya speakers would need to be hired to accommodate the state’s large bureaucracy. This would include everything from driver’s licenses to the payment of property taxes.

“Nobody is saying that this would be easy, but it’s a move certainly worth seriously considering from a social justice perspective,” said state representative Gasparl Quintal Parra.

The move comes on the heels of a 2022 decision by the state Congress, which recognizes the Yucatec-Maya language as an intrinsic part of the state’s cultural heritage.

Though the Yucatec-Maya language has now used the Latin script for hundreds of years, interest in reviving its more ancient hieroglyphic form is on the rise.

Despite the widely held belief that the Mayan language is in decline, speakers of this Prehispanic family of languages exceed 6.5 million.

Recent census data show that approximately 560,000 people in Yucatán speak Yucatec-Maya, mostly as their first language.

The Yucatec-Maya language is also spoken widely in the neighboring states of Campeche and Quintana Roo.

Other Mayan languages and dialects are also spoken widely in Chiapas, parts of Tabasco, and the Central American nations of Guatemala and Belize — as well as large diasporas in the United States and Canada.

It is also not uncommon, especially in villages in the interior of the state, to meet people who do not speak Spanish, which makes access to government services a hassle.

Despite heavily promoting the Maya culture as a draw for tourism, racism towards Maya people remains a persistent problem in Yucatán, with many individuals feeling uncomfortable speaking it outside of their homes and communities.

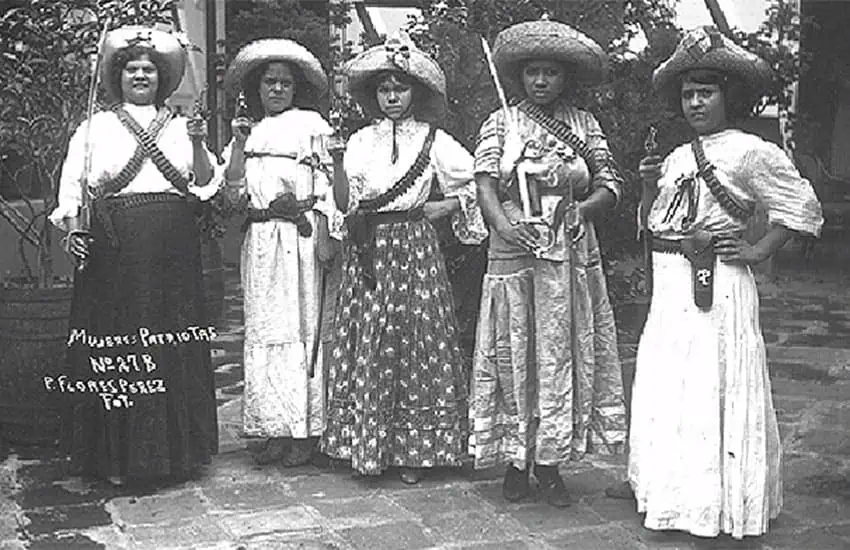

Long after the Revolution’s end, a trans soldier fought for recognition

The history of Mexico has many stories about the heroes and events of the Mexican Revolution but one military leader was, until recently, rarely mentioned: the transgender soldier Colonel Amelio Robles — whose gender identity was not generally a known fact for much of Mexico’s history but was known by the Mexican Army.

Robles lived his life as a man from the age of 24 until his death at the age of 95. Shortly before his death, he was finally recognized for his service to the country and decorated as a hero of the Mexican Revolution.

His story became better known in 2022 with the publication of Ignacio Casas’ novel, “Amelio, Mi Coronel.” (Amelio, My Colonel).

“Robles was a very complex person,” Casas states. “In order to understand him, you have to look at his life in three phases — his youth, the Mexican Revolution years, and the post-revolution years.”

Amelio was born Malaquías Amelia de Jesús Robles Ávila in 1889 in Xochipala, Guerrero. The youngest of three children, Robles was from the country but not poor — his father was a well-to-do rancher and owned a mezcal distillery. Robles received a Catholic education from the Society of the Daughters of Mary of the Miraculous Medal, a congregation dedicated to the spiritual formation of young girls.

Robles was raised learning how to sew, cook and iron, but preferred riding horses, lassoing cattle and practicing marksmanship. After his father died, Robles became rebellious. His mother remarried, and Robles didn’t get along with his stepfather and three half-brothers; he reportedly was jailed for killing one of his half-brothers, although this isn’t proven.

In 1912, at the age of 23, Robles joined the revolutionary struggle in the Zapatista army, not because of his revolutionary beliefs but because it offered him freedom from the conservative rural society where he lived.

The war was forever life-changing for Robles, whom fellow soldiers initially called “La Güera Amelia.” However, Robles began to dress like a man, took the name Amelio and insisted — often at gunpoint — that he be addressed using male pronouns, according to a history of Robles written by the Ministry of Culture.

Robles rose quickly through the ranks, attaining the rank of colonel. In his personal logs, he listed participation in 70 battles — gaining the respect of fellow revolutionaries with his prowess as a military leader — commanding up to 1,000 soldiers. He was a skilled horseman, an excellent marksman and a fearless soldier.

There are numerous examples of women who joined the revolution and fought alongside male soldiers, wearing men’s clothing and even taking male names. Petra Herrera, credited with seizing Torreón as a Villista soldier in 1914, was known as Pedro Herrera. Ángela Jiménez, who fought with the Zapatistas and Villistas, became Ángel Jiménez.

But unlike these women, Robles embraced his masculinity and identified as a man until his death in 1984 at the age of 95. In the 1950s, he even managed to alter records to say that he had been born male.

After the military phase of the revolution ended in 1920, Robles supported revolutionary general Álvaro Obregón, who became president (1920–1924). He took up arms and fought with Obregón forces in the Agua Prieta Revolt, which brought an end to the government of Venustiano Carranza.

He then settled in Iguala for a time afterwards but was attacked by a group of men attempting to reveal his body as that of a woman. Robles killed two men in self-defense and was incarcerated for a second time, confined to the women’s area of the jail.

In the 1930s, Robles met Ángela Torres and married, settling into civilian life and later adopting a daughter, Regula Robles Torres. He remained politically active, joining the Socialist Party of Guerrero and the League of Agrarian Communities. But he still had not received the recognition he deserved as a revolutionary leader.

Robles was determined to get that recognition. In 1948, he finally received the medical certificate required to officially enter the Confederation of Veterans of the Revolution — confirming that he had taken six bullet wounds in battle.

In 1955, he also began the process of changing his service files to identify him as Amelio Robles rather than his prior name; he even had a false birth certificate inserted into his personal files at Mexico’s military archives.

According to historian Gabriela Cano, “The [false] document attests to the birth of the child Amelio Malaquías Robles Ávila. Except for the baby’s name and sex, all other data coincides with the original birth certificate from the Zumpango del Río civil registry book.”

Robles was in his 80s when the Ministry of National Defense finally recognized him as a veteran of the Mexican Revolution. Shortly thereafter, he received the Legionary of Honor of the Mexican Army and the Medal of Revolutionary Merit.

Before his death, he was recognized by three former presidents — Adolfo López Mateos, Manuel Ávila Camacho and Luis Echeverría — as an outstanding revolutionary.

But for all his attempts to bury his past life as a woman, some still refused to accept him as a man: his childhood home became the Coronela Amelia Robles Museum.

Perhaps as a sign that Mexico is changing—becoming more tolerant and supportive of gender diversity—the Ministry of Culture’s website states that “the participation in the [Mexican] Revolution [of Amelio Robles] as a transgender man whose identity was recognized and who was a colonel marks a milestone. And contrary to what is commonly thought, it indicates that people of gender diversity have always been present and have participated in many historical events of the country.”

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance research and writing

A Caribbean island’s quest to become the world’s first climate-resilient nation

By Jose Alison Kentish19th April 2023

The Caribbean island of Dominica is one of the world’s most at-risk places from climate change. Can it fulfil plans to become the world’s first climate-resilient nation?

On a sunny Monday morning in September 2017, 67-year-old Faustulus Frederick was adding the finishing touches to a traditional wooden sculpture at his home in Salybia, on the Caribbean island of Dominica.

The small village of Salybia is one of eight that make up the 3,700-acre (1,500-hectare) Kalinago Territory – the home of Dominica’s indigenous people. At the territory’s highest elevations, lookout points provide sweeping views of the tempestuous Atlantic Ocean thousands of feet below.

Frederick is an artist and former teacher who served his people as Kalinago Chief when he was just 25 years old. His paintings depict life and tradition in the Territory. His mural on the wall of the community’s Catholic church is a breathtaking landmark, along with the church’s altar – a carved canoe.

But as he added paint to the face on his latest piece, an emergency update blared on a nearby radio.

“The weather announcer said we should prepare our things and get ready to move to the shelter, which is the primary school,” he tells me as we sit in a classroom at that shelter – his home since 2017.

ADVERTISEMENT

Warnings are important for everyone…They let places be habitable – Ilan Kelman

Frederick grabbed some clothes, papers and his artwork and headed over. There were only a few hours to spare.

The storm was first announced to residents of the small island as a tropical depression on 16 September, but within two days heightened ocean surface temperature and low wind shear led it to intensify to a category five superstorm, the strongest possible hurricane, which was named Hurricane Maria.

When it made landfall in Dominica it hit the Kalinago Territory first and hit it hard. It claimed lives island-wide and cost Dominica over 3.5 billion Eastern Caribbean Dollars (£1bn/$1.3bn), equivalent to 226% of its GDP in 2016, in losses and damages. “It was the toughest hurricane we ever faced,” says Frederick.

Dominica is one of the most disaster-vulnerable countries on Earth, meaning the country faces a choice between building resilience or risking becoming locked in an unsustainable cycle of destruction and rebuilding from hazards that could eventually make living there unfeasible.

After two of the country’s most costly natural disasters struck within two years of each other (2015 and 2017), Dominica’s prime minister declared the country had found itself “on the front line of the war on climate change” and announced plans to make Dominica “the world’s first climate-resilient nation“. Building resilience into every facet of society was essential to ensure the island remains habitable, he said.

Among the key measures to mainstream resilience is Dominica’s early warning system – a means to warn residents in advance about dangerous weather events, allowing them time to make what can be life-saving preparations, such as moving to higher ground. Dominica’s unique system includes a grassroots approach of support and communication using traditional conch shells.

Faustulus Frederick works on a Calabash carving in the shelter he has called home since Hurricane Maria in 2017 (Credit: Jose Alison Kentish)

“Warnings are important for everyone. They save lives. They support livelihoods. They let places be habitable,” says Ilan Kelman, deputy director of the University College London (UCL) Warning Research Centre, the world’s first research centre dedicated to the science of warnings.

Protecting the everyday lives of Dominicans means implementing early warnings across communities and integrating them with other protections. In the long term, though, the big question that lingers is whether this will be enough.

The value of warnings

Small island developing states like Dominica are disproportionately impacted by climate change, meaning they stand to lose even more than other countries if the global community and big greenhouse gas emitters fail to meet commitments to cut emissions.

The adaptation limits of some islands may be exceeded well before 2100, says Shobha Maharaj, a climate impacts scientist and lead author of the small islands chapter in the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report. This means some small islands face a threat to their very liveability, due to both sea-level rise and exposure to repeated extreme weather events.

The IPCC painted a worrying picture of how small islands are already feeling the impacts of climate change. In Dominica, rising sea levels that increase the risk of storm surges and the increase in the strength of hurricanes are among the principal climate change concerns, alongside floods and landslides. A 2019 study concluded that a storm of Maria’s magnitude is nearly five times as likely to form now as during the 1950s.

The IPCC singles out early warning systems as a key pillar of climate adaptation across risk areas from hurricanes and flooding to extreme heat and the spread of disease across the world. It credits the systems for saving lives following the devastating European heatwave of 2003, and notes that, in the case of flood risk, they may be the only measure to reduce casualties.

At the Cop27 climate conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt last year, UN Secretary-General António Guterres unveiled a plan to ensure everyone on the planet is protected by early warning systems within the next five years.

“Vulnerable communities in climate hotspots are being blindsided by cascading climate disasters without any means of prior alert,” he said, noting that countries with limited early warning coverage have disaster mortality eight times higher than countries with high coverage.

Dominica’s case is especially tricky due to its mountainous topography and therefore the complexity of generating accurate extreme weather forecasts – particularly for floods, says Emily Wilkinson, a senior research fellow at the Overseas Development Institute, a London-based think tank. “Many communities get completely cut off by tropical cyclones, sometimes for weeks.”

Dominica is one of the most disaster-prone islands, with flooding one of the most common hazards (Credit: Jose Alison Kentish)

Standing outside the hurricane shelter he still calls home, Frederick tells me radio bulletins played a key part in warning people about Hurricane Maria. “We always listen to the weather forecast. It was the forecast and warning to move fast to the shelter that helped us.”

Neighbours also scrambled to each other’s houses to spread the word, he says. He himself helped an elderly man to the shelter during the disaster.

This element of neighbourly communication is hugely important for early warning systems, says Jennifer Trivedi, assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Delaware’s Disaster Research Center.

“Often, when I ask people in the field where they heard about an incoming hurricane, or changing floodwaters, they talk about hearing it from friends or neighbours,” she says. “Someone knocked on their door. A friend called their house. They heard about it at church. Those networks are essential because people know them, they trust them.”

This intricate communication chain provides important layers to reach people in more ways, she adds, over and above warnings sent to smartphones. “We can’t expect that will be the only warning system. Many people around the world don’t have [a smartphone], don’t use all its capabilities, or maybe they’re in an area that doesn’t get a signal as well.”

Frederick Donaldson, the disaster coordinator for the territory and a member of the Kalinago community, says Dominica’s cascade system for early warnings has been used for centuries by indigenous people.

Keeping areas habitable is a decision that has to be made not only in local city halls, but also in spaces like the United Nations – Jennifer Trivedi

Today, the system starts with urgent official information at the national level which is trickled down through various stages until it reaches the community. In the Kalinago territory, the council, the local governing authority led by the Kalinago chief, is at the heart of the system.

“It receives information from the National Disaster Office,” says Donaldson. “The emergency warning system then kicks into gear, with each hamlet head receiving instructions, and they take the information throughout the community. Each hamlet has five or six people trained in community emergency response.”

The network relaying storm information uses a mix of modern and traditional methods.

On the modern side, an emergency response chat group is used by the country’s disaster officials to alert the council, which moves to communicate it to the community, says Donaldson. “We head out with a PA [public address] system, drive around the territory and blast messages.” Alerts are also sent out via radio bulletins and smartphones.

And then there are the conch shells. Conch shell blowing has been used for hundreds of years by the Kalinago for communication. Nationally, the unique sound of the conch shell blaring through a neighbourhood indicates that there is fresh fish for sale. Ahead of urgent news, the short upbeat calls for fish are replaced with long, drawn out bellows.

An integrated system

Maharaj says many small islands remain highly challenged in building and sustaining integrated, people-centred, end-to-end warning systems, although improvements have been made in detecting, monitoring and forecasting severe weather.

Of course, early warning systems are only one in an array of important tools to protect islands from climate impacts. They work best in tandem with effective disaster risk management and resilient infrastructure – such as shelters.

A model Kalinago structure as part of a project by Faustulus Frederick to forge resiliency based in local culture (Credit: Jose Alison Kentish)

Following Hurricane Maria, the Climate Resilience Execution Agency of Dominica (Cread) was established with a deep focus on disaster planning and early warning systems. Its community emergency readiness programme assessed the vulnerability of all communities in Dominica to different natural hazards, says Wilkinson, who has been an advisor to Cread since 2019.

“It prioritises which communities are the most vulnerable and what kind of support they would need, including things like stabilising slopes in communities that would often get cut off by heavy rainfall and landslides.”

Other small island states like Union Island have embraced ecosystem restoration as a buffer against potentially deadly storm surges, another essential adaptation strategy which Dominica is embarking on.

With 90% of its population living in coastal communities, Dominica has also erected several sea and river walls to protect communities from flooding, and aims to make its healthcare facilities more resilient to extreme weather events. Other critical infrastructure like new roads and bridges are being built to better withstand natural hazards.

And then there are the buildings.

Two years before Hurricane Maria, Tropical Storm Erika dumped 12in (30cm) of rain on the island in 12 hours. Residents report hearing howling winds and deafening rumbling as the heavy rainfall made light work of rocks, roofs, vehicles and many homes during the night.

The community was wiped out. In the days following the storm, we were evacuated by boat. I left with only my backpack – Sarwan Gregoire

The storm claimed 20 lives in the hardest-hit village, the south-eastern community of Petite Savanne. Residents were evacuated and the village declared uninhabitable. Over 800 families bade farewell to the village they called home.

“It was tough,” says 20-year-old Sarwan Gregoire, a primary school teacher, who, then 13, was among them. “The community was wiped out. In the days following the storm, we were evacuated by boat. I left with only my backpack.”

Gregoire now lives in the nearby community of Bellevue Chopin, in a government-built housing development. Contractors follow disaster-resistant construction designs, in keeping with protocols under Dominica’s 2020-30 Climate Resilience and Recovery Plan.

Meanwhile, revisions to Dominica’s building code last year mean only homes and buildings that can withstand natural disasters will be approved for construction, according to Vince Henderson, Dominica’s former minister for planning.

Such apartments address gaps in construction which disaster officials like Donaldson say compounded the impact of Hurricane Maria in the Kalinago Territory. “With the intensity of the hurricane and dealing with the impacts of climate change, resilient housing became a priority.”

The road ahead

Dominica is determined to set an example of a small island state successfully confronting climate change. The protection of ecosystems, erection of sea defences and building resilience in infrastructure are all part of a mission to protect lives and livelihoods.

It is an urgent mission. Mia Mottley, the prime minister of Dominica’s sister island Barbados, has warned that large-scale migration from the small states of the Caribbean will be a reality in the next decades without emissions cuts and finance for robust climate and resilience projects.

‘Climate-resilient’ homes in Belle View Chopin, Dominica, are now home to those displaced by Storm Erika (Credit: Jose Alison Kentish)

So what more can islands like Dominica do to remain habitable?

First and foremost, address data gaps, says Maharaj. “We don’t have data on future sea-level rise and wave climate projections for most islands. Think about that. We’re so exposed and vulnerable on our coastlines.” Islands also need more information on the value of ecosystems services to tackling climate change, she says, and studies to model their future habitability. And there needs to be clear, direct communication chains from scientists to policymakers to ensure they are aware of what’s lacking and the consequences, she adds.

For Trivedi, habitability ultimately hinges on cooperation between people on many different levels – from local cultural decision-making to international policy changes. “Keeping areas habitable is a decision that has to be made not only in local city halls, but also in spaces like the United Nations.”

Warning systems that cut across multiple hazards are also key, says Fearnley, alongside investments in public education. “It’s thinking about the whole process and having that dialogue repeated every single year, refreshing the relationships, refreshing the knowledge to embed the warning system as part of the everyday fabric of life.”

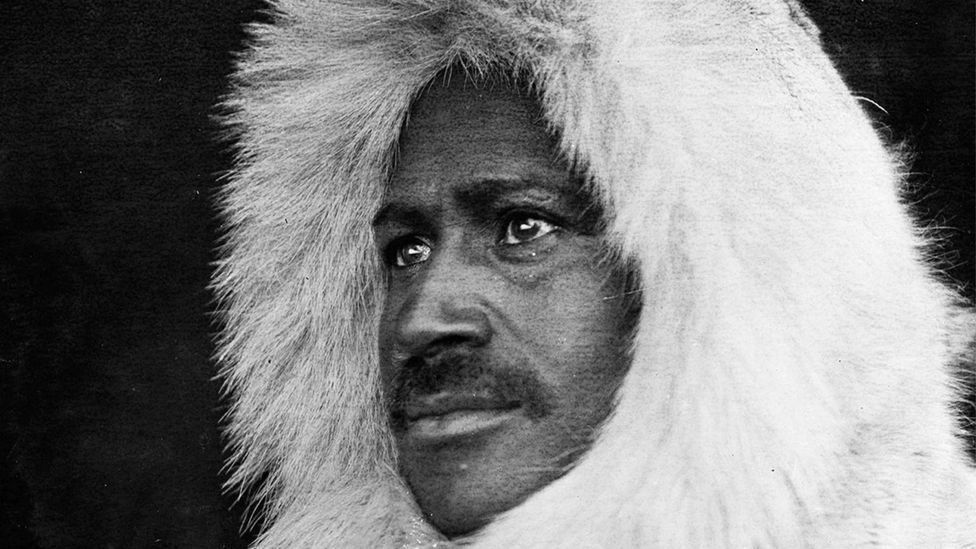

Matthew Henson: The US’ unsung Black explorer

By Robert Isenberg19th April 2023

While other explorers may claim credit for discovering the North Pole, an unsung and largely forgotten former sharecropper has as good a case as anyone.

Located just outside Washington DC in Montgomery County, Maryland, the 116-acre Matthew Henson State Park Stream Valley Park is a leafy, wooded oasis surrounded by suburban sprawl. As you enter, the hum of traffic soon fades away, and all hikers, joggers and bikers can see are grass and trees. A 4.2-mile paved trail gently curves through the forest, before an elevated wooden boardwalk carries it above a wetland. Birds chirp overhead, and deer and wild turkeys are a common sight.

You could walk this trail every day and never know who Matthew Henson was – unless you stopped at a certain trailside sign that displays a bulleted timeline of Henson’s life:

• 1866: Born in Charles County, Maryland.

• 1879-1884: Joins the crew of the ship Katie Hines as a cabin boy and explores the world.

• 1887: Joins Robert E Peary to assist in the survey of Nicaragua for a possible canal.

Then, in the middle of this biography, there’s a surprising detail:

• 1909: Reaches the North Pole with Peary and plants the American flag.

Born into a family of sharecroppers, Henson later set sail for the North Pole (Credit: Everett Collection Inc/Alamy)

The sign is topped with a photograph of Henson wrapped in furs, a hood pulled over his head. His brow is soberly furrowed, and he wears a bushy mustache. His appearance fits the archetype of the polar explorer in every way but one: Henson was Black.

“As a kid growing up in school, I never heard of Matthew Henson,” said JR Harris, who is also African American and serves on the board of directors of the Explorers Club, which has inspired some of the world’s greatest adventurers. “A lot of people assume that Matthew Henson was somebody I looked up to back in the day, and that’s just not true. All we heard was that the North Pole was discovered by Robert Peary.”

Henson’s life reads like a Victorian adventure novel. Born to a family of sharecroppers, Henson worked odd jobs before he joined the crew of a merchant ship and sailed to distant continents. His first mentor was one Captain Childs, who trained the adolescent Henson for a life at sea and even taught him to read. When Childs died in 1883, Henson again struggled to make a living – until a fateful encounter with Robert Peary in 1887. They first crossed paths at a haberdashery in Washington DC where Henson worked. Commander Peary, an engineer with the US Navy, was impressed with the young stock boy and he invited Henson to serve as his assistant on a survey mission to Nicaragua later that year.

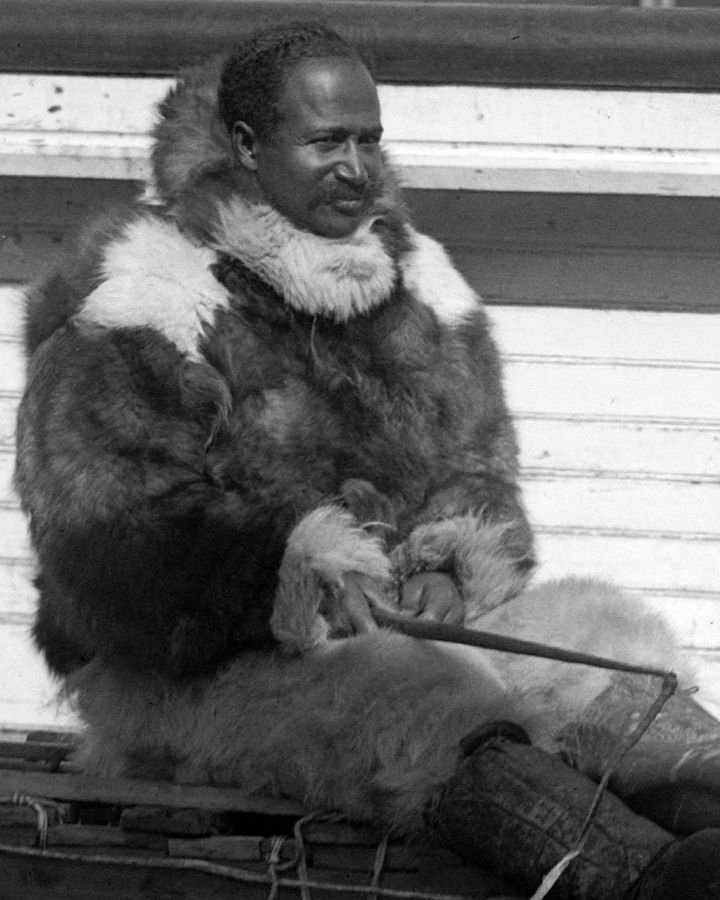

The pivotal stage of Henson’s career unfolded over an 18-year period starting in 1891, when he accompanied Peary to the Arctic Circle in search of the North Pole. As one of the last unexplored corners on Earth, the quest to physically reach the world’s northernmost point had lured explorers for centuries – many of whom had fantasised about standing on top of the planet. Yet, the Pole’s harsh weather and ship-crushing ice floes had repelled all human visitors, even the Inuit.

Peary took Henson under his wing and invited him to accompany the Commander to the Arctic Circle (Credit: Niday Picture Library/Alamy)

Peary was the established leader of these expeditions, raising money and organising teams. Henson accompanied Peary on every journey but one, spending years of his life in the field. In Greenland, Henson bonded with the Inughuit, the northernmost people in North America and part of the Greenlandic Inuit peoples; he learned to build igloos and sledges, and he became fluent in the Inuktun language. He hunted polar animals with a rifle, a life-saving skill when provisions ran low. Most impressively, Henson learned the art of mushing.

“He is a better dog driver and handles a sledge better than any man living, except some of the best [Inuit] hunters,” Peary wrote of Henson. “I couldn’t get along without him.”

Over the course of seven attempts from 1891 to 1909, Henson was Peary’s closest collaborator. The Arctic was unforgiving, and the two men nearly froze or starved on several occasions. Peary lost many of his toes to frostbite; Henson once broke through the ice and would have drowned had his Inuit friend Ootah not pulled him from the freezing water. The men weathered catastrophic storms and never-ending technical snafus. They refined their process again and again, until their final expedition in 1909. As supplies ran low and they were roughly 134 miles from the Pole, Peary ordered everyone in his 50-person party to return to their ship, except for four Inuits and Henson.

According to a Smithsonian article, several days later on 6 April 1909, after an arduous trek through the tundra, Henson allegedly told Peary that he had a “feeling” they were now at the Pole. Henson said that Peary then dug into his coat, pulled out a folded American flag sewn by his wife and fastened it to a staff that he stuck atop an igloo. The following day, Henson said Peary determined their location with a sextant, placed a note and the US flag in an empty tin and buried it in the ice. The men then turned back toward the ship to head home.

After Henson told Peary he had a “feeling” they’d reached the North Pole, Peary determined their location with a sextant (Credit: Alpha Stock/Alamy)

“Another world’s accomplishment was done and finished,” wrote Henson in his 1912 memoir, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole. “And as in the past, from the beginning of history, wherever the world’s work was done by a white man, he had been accompanied by a colored man.”

Yet Henson’s moment of glory was short-lived. For the next century, historians would be sceptical about Henson, who returned to the United States at the height of Jim Crow hostility. Peary wrote an effusive foreword to Henson’s book, arguing that “race, color, or bringing-up, or environment, count nothing against a determined heart, if it is backed and aided by intelligence”. Still, Peary gladly received most accolades for reaching the Pole, while Henson’s name faded from the public eye.

Historians debate whether Peary’s surveying was correct – plus there’s dispute as to whether he was even the first explorer to get there – but most agree that he couldn’t have ventured so far north without Henson, who fully embraced Inuit life and studied millennia-old survival skills. Henson adapted Inuit tools, such as fur garments and dog-driven sledges.

“The [Inuit] people really liked him,” said Harris, who has himself embarked on scores of self-supported solo hikes in wilderness areas around the world. Like Henson, Harris has forged relationships with Indigenous people in remote locations and appreciates this early attempt at cultural anthropology. “Peary was kind of standoffish, and he appreciated that someone in his party could deal with the Inuit population and could establish good relations.”

Henson embraced Inuit culture during the Arctic expeditions (Credit: Everett Collection Inc/Alamy)

Still, it wasn’t until 1937 that Henson was admitted as a member of the Explorers Club. He eventually received honours from presidents Harry S Truman and Dwight D Eisenhower, but only towards the end of his life. Henson was ultimately interred at Arlington National Cemetery, where a special monument now stands, but it wasn’t erected until 1988 – 33 years after his death. Today, a handful of landmarks are named after him: Matthew Henson State Park, several Maryland public schools and the USNS Henson, a 3,000-ton research vessel that conducts oceanographic surveying.

For decades, Henson supporters have kindled the memory of his achievement – and attempted to trace the full breadth of his legacy. His most passionate advocate was the late Dr S Allen Counter, a Boston-based neurologist and fellow member of the Explorers Club. Not only did Counter petition Arlington for the monument, but he discovered unknown branches of Henson’s family tree in Greenland – several of his Inuit descendants are still alive today. He documented this lineage in his book, North Pole Legacy.

“The story resonated with my father for obvious reasons,” said Philippa Counter, Allen’s daughter. “They were both explorers. Henson was this unsung hero who didn’t get recognised for going to the North Pole. He thought, ‘This is a story I absolutely have to tell’.”

Dr Counter passed away in 2017, but others have taken up the torch. The Explorers Club started a Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Committee, with JR Harris as its chair. In 2022, the Club posthumously admitted four new members: Seegloo, Egingwah, Ooqueah and Ootah, the Inuit men who accompanied Henson and Peary on their final expedition.

It was only towards the end of his life that Henson began to be recognised (Credit: Everett Collection Inc/Alamy)

“In my opinion, they’re all co-discoverers of the North Pole, all six of them,” said Harris. “Those four guys are finally getting the recognition they deserve.”

Meanwhile, in Brunswick, Maine, the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum is currently moving buildings. The museum belongs to Bowdoin College, alma mater to both Peary and fellow Arctic explorer Donald Baxter MacMillan. Since it opened in 1967, the museum has showcased Henson artefacts, including archival photos, a sledge he built himself and a rare television interview from the 1950s. Patrons have always been welcomed with painted portraits of Peary and MacMillan, positioned side-by-side at the entrance. However, when the new space opens in May 2023, it will have an important addition: an enlarged photograph of Henson, dressed in his trademark furs, displayed next to them.

Rediscovering America is a BBC Travel series that tells the inspiring stories of forgotten, overlooked or misunderstood aspects of the US, flipping the script on familiar history, cultures and communities.

Tixkokob a hammock manufacturing town

These hammocks used to be hung between trunks in the past, however this has been modified over time

and today in order to hang them from the walls of a house you need the help of metal rings, which are

called Alcayatas.

Tixkokob is the only one of the 106 municipalities in Yucatán where more than 30 workshops are dedicated to the production of hammocks of various sizes and models, personalized with names of the client, as well as with symbols

and images of choice. The manufacture of this typical resting device is totally handmade and can take from eight days to three weeks, depending on the size and model, although there are specific cases in which, due to their details, they can take up to 60 days to be made.

The origin of the hammock has not been defined yet, but it is known that it existed at least two centuries before the legacy of the Spanish. The word hammock comes from the Taino language, which means “fish net”.

In the Mayan region they were made from the bark of the Hamak tree and later with silver from Sisal. The green fiber of the henequen tree was used to weave them, mixed with cotton, until the present day, in which nylon thread is used.

These are the different types of hammocks you can find in Tixkokob:

Crochet, Traditional hammocks, Swings, Whistles and Banqui.

Hammocks are a resistant weaving that is used as a resting and sleeping device; the hammocks have a

manufacturing origin within the Central American indigenous people, and such is their use that they

have been commercialized all over the world.

Rare statue of Mayan god K’awiil discovered on Maya Train route

Archaeologists performing rescue work on section 7 of the Maya Train route have found a rare stone sculpture of the Mayan god K’awil, a deity linked to power, abundance and prosperity.

The discovery was announced by Diego Prieto Hernández, general director of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), during President López Obrador’s morning press conference.

“This finding is very important because there are few sculptural representations of the god K’awil; so far, we only know three in Tikal, Guatemala, and this is one of the first to appear in Mexican territory,” Prieto said.

He explained that the deity is more commonly seen represented in paintings, reliefs and Mayan codices. This rare three-dimensional image was found on the head of an urn whose body shows the face of a different deity, possibly linked to the sun.

Prieto said AMLO had been shown the piece during a tour last weekend to inspect progress on section 7 of the Maya Train, which runs between Bacalar, Quintana Roo and Escárcega, Campeche.

He added that archaeological rescue work is now concentrated on sections 6 and 7 of the train’s route, as work is now completed on sections 1 to 5, between Palenque, Chiapas and Tulum.

“Work is still being done on complementary projects, such as the collection and cleaning of archaeological materials, their classification and ordering,” Prieto said.

“All this work should lead to analysis of the vast information, preparation of academic reports and a large international research symposium on the Mayan civilization, which will be organized for this year.”

As of April 27, the INAH has registered and preserved as part of the Maya Train archaeological rescue project:

- 48,971 ancient buildings or foundations

- 896,449 ceramic fragments

- 1,817 movable objects

- 491 human remains

- 1,307 natural features, such as caves and cenotes.

Other notable discoveries made during construction include a 1,000-year-old Maya canoe at the San Andrés archaeological site near Chichén Itzá, an 8,000-year-old human skeleton in a cenote near Tulum, and a previously unknown archaeological site of more than 300 buildings in Quintana Roo, dubbed Paamul II.

Prieto has previously said that a new museum will be constructed in Mérida that will be dedicated to discoveries unearthed during the construction of the Maya Train. The INAH is also analyzing the findings at its laboratory in Chetumal, which Prieto said would nourish the study of Mayan civilizations for the next 25 years.

However, while the archaeological rescue process is thought to be progressing well, the Maya Train continues to face strong resistance from environmentalists, who believe the project will do irreversible damage to the region’s unique ecosystems and subterranean lakes.

With reports from Aristegui Noticias

—

Recent Comments